|

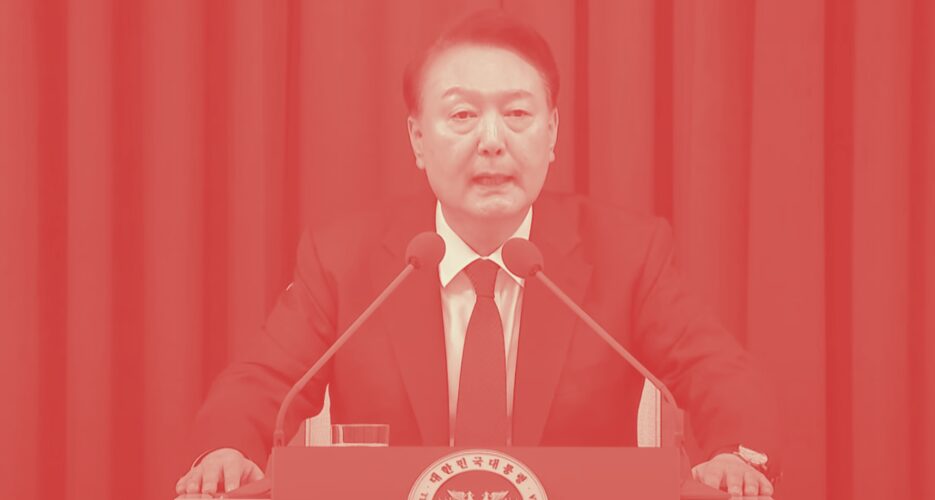

Analysis What Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law gambit means for the Korean PeninsulaSouth Korean leader’s declaration risks triggering domestic unrest, while opening door to North Korean escalation  South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol’s sudden imposition of martial law on Tuesday night represents a watershed moment for South Korea’s democracy, one that could trigger severe political turmoil and violent unrest in the days ahead. By citing a need to “eradicate pro-North Korean forces” and uphold constitutional order, Yoon has stepped well beyond the normal bounds of his authority and set the stage for a major democratic crisis. The declaration raises the risk that Yoon could seek to use the military to crack down on civil liberties and even use violence against protesters © Korea Risk Group. All rights reserved. |

The ultimate resources for professionals working on North Korea